The ecologist jumps into the deep, scary waters of machine learning...

Misconceptions

About two years ago, when I started thinking more deeply about the possibility of a career in data science, I made a concerted effort to figure out where my gaps in knowledge were (a phrase we often overuse in science, in my opinion - it feels a bit tired) and what my weaknesses were. I felt strong in R, felt that I had experience munging messy data, and felt strong in my statistical background, but I had virtually no experience with machine learning (ML), which seemed to be all anyone was talking about when I got on the web and started looking at data science positions.

To an outsider at first pass, it seemed like magic - really complex algorithms that could predict outcomes with super-complicated sets of data. I didn’t know the math, I didn’t know the toolkit, and it looked like an unknowable world - the realm of AI, and self-driving cars, and SkyNet.

Right?

It isn’t. (…other than it’s related to AI - though these two things are often confused, used for self-driving cars, and the fictional SkyNet is apparently an Artificial Neural Net…I didn’t know this prior to writing this post).

It took time, and a bit of tenacity, and boat-load of playing around and messing things up, but these are traits most folks in academia acquire. In this post, I want to break down the fundamentals of machine learning (as I see them - I have soooooo much more to learn) from the perspective of an insect-ecologist, with the hope of demystifying some of magic, while outlining some resources I felt were useful.

The fundamentals

- Prediction versus Explanation

- Training and Testing

Prediction vs. Explanation

This was the single biggest mental hurdle for me. My training as a research scientist gave me a toolkit of statistical analyses to use to explain data - to understand what caused the patterns we see in the natural world. This toolkit provides a robust way to answer questions about data and experiments:

- Do plants that are attacked by lots of caterpillars give off different scents than those that are attacked by fewer caterpillars (and what about unattacked plants)?

- Do parasitoid flies allocate more energy to their cognitive or their reproductive systems when they’re competing for food as maggots within a host?

These questions are about explanation, and are fundamentally different from the kinds of questions that machine learning typically addresses. Some examples of ML questions:

- What is the likelihood that this uploaded image depicts something (nudity, violence, etc.) that goes against a platform’s (youtube, facebook, etc.) terms of service?

- What types of movies would a customer be interested in, given other movies they’ve watched, the time of year, and where they live?

- What is the price of a hundred-pound bag of garbanzo beans going to be 6 months from now, given it’s February, and I know the current price and a bit about the market?

The key difference? It’s all about prediction, not explanation. The goal is entirely different. This fundamental difference is one of the things that seems to have driven the development of algorithms that are really good at predicting things, but are so complex that humans struggle with interpreting them, or figuring out what underlying variable interactions produce the predictions (I’m looking at you, deep neural nets, support vector machines and extreme gradient boosting). These types of algorithms are frequently called black box algorithms.

This concept was initially pretty frustrating as a research scientist interested in explanation-type questions. “What do you mean you don’t know which variables are the most important, or have any understanding of how they interact to make predictions!?” ARGHHHHGHHHHHH!!

But, sometimes you just want to be able to predict something really well! It’s a powerful tool that can be crucial for businesses that aim to provide customers with the best experience possible (think about Netflix, YouTube or Amazon).

A caveat

All of this is an open field of discussion - and it’s a spectrum of black boxes and… whatever the opposite is? White… boxes? Anyway.

Case in point - this lengthy discussion on stack exchange. People smarter than I am are making headway at finding ways to unpackage black-box algorithms, and the truth is that sometimes, businesses and other entities want explanation-level insight about prediction models - so black box algorithms might not always be the best choice.

The point is that different algorithms have different levels of interpretability, and different abilities to make predictions on a given data set. It all comes down to what kinds of questions and answers a data scientist is looking for.

Training and Testing

Usually, as an biologist (excluding those pesky genomicists who have all the data they can shake a stick at), we’re data limited. You’ve spent the time, resources and manpower to collect as much data as you can among all your experimental (and control) treatments, and you’re going to use every damn piece of it to explain the phenomena you’re interested in, test hypotheses and provide evidence for your predictions.

But there is a problem here - what if the conclusions you draw from the statistical models you’ve built with your data are singular to your data? You can’t know, because… you’ve used all the data you have to build the best model you can. This problem is called overfitting.

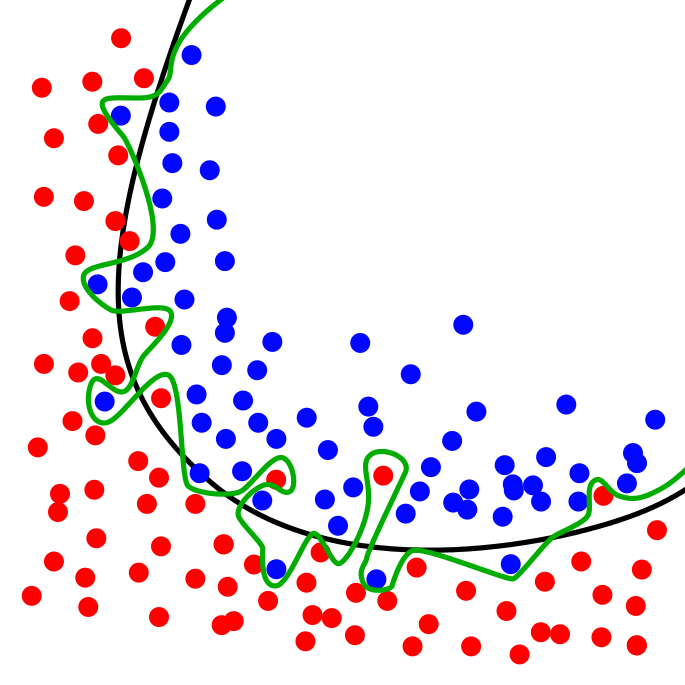

I love this figure on overfitting from wikipedia:

The green line represents an overfit model, and the black line represents a good regularized model. The green model does a kick ass job at predicting the division of red and blue dots with the training data, but might do a poor job on a new set of data - it’s too connected to the eccentricities of the data set it was trained on.

What if you had a lot of data to work with, how might you deal with this overfitting problem? First, you could split your data (randomly) into a training and test set. Build your models on the training set and see how well it does at predicting outcomes on the test set. This would give you a good feel for how the model would perform on brand-new, out of sample data.

Additionally, you could divide your training data into a bunch of different randomly-assigned mini-data sets, and building and asessing models on this mini-sets to get an of how well a model will do on new data: this technique is called k-fold cross-validation where k is equal to the number of mini-datasets we break the data into. The best case scenario is when you have loads of data to do both k-fold cross-validation and a big chunk of data you can exclude for final model-testing.

There are great tools in R to do all of this with, my favorite being the amazing caret package.

Conclusions

There is still a lot to talk about (hopefully in future posts), such as what algorithms to choose and the merits of different platforms. Hopefully this is was an informative walk-through of the basics of ML through the eyes of a relatively recent learner with the perspective of an ecologist. There are a lot of wonderful resources out there for scientists looking to explore ML:

Machine Learning with R - I plowed through this in the last year. It’s a clear and useful introduction to a lot of the basic ideas and algorithms, with nice exercises and examples.

Machine Learning Modelling Cheatsheet - A nice overview of the differnt types of models available, their packages and some sample code.

DataCamp - I’ve worked through many (but not all) of the Machine Learning courses in R. Overall, they’re fantastic - I particularly enjoyed the machine learning toolbox course, which focused on how to use caret.

Next time, I’ll demonstrate some of the machine learning tools I used in the bean-market prediction project, with particular focus on splitting the data into training and test sets and setting up cross-validation in caret.

Cheers!