A broker simulation leveraging the predictive bean model

Hi there!

It’s been a while! Sorry for the delay on posting, but things have been a bit crazy with the transition between the end of the semester at UA and moving into Summer research projects! I’ve also become a little obsessed with the Tidy Tuesday challenge on Twitter - it’s a cool project for the #r4ds (R for Data Science) community that sends out weekly datasets that Twitterfolks can munge and visualize with the fantastic tidyverse packages. If you’re interested, you can check out my submissions on Twitter or the Tidy Tuesday repo on GitHub.

Enough of a preamble. Where were we? Oh right. Beans.

What happens if we had our bean model to make investments in real life?

This post comes out of discussion with friends and family after building the predictive bean model - what sort of real world application does this have? Sure, it seems like a reasonable financially beneficial thing to be able to predict markets with a high degree of accuracy, but what does that actually mean to someone interested in throwing some money at buying and selling dry beans?

Well, I thought it might be useful to try and simulate an investment scenario. The rules are fairly simple:

- You start with $10k to invest

- You can’t spend more than 33% of your capital on a given week

- Of that 33%, you spend as much as you can if the model predicts that the price will be higher in 6 months than the current price, otherwise you don’t buy anything

- You sell all of those beans 6 months down the line at whatever the market price is

- You can’t spend more than 100k on one purchase (optimistic that you’ll have this much bank eventually)

Let’s build the simulation (it’s also worth noting here that we’re preforming this simulation on the out-of-sample test data).

The simulation

Reading in the data and prepping it (code from two posts ago)

#loading appropriate packages

library(caret)

library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

#install.packages("scales")

library(scales)

#reading in the bean_master file

bean_master_import = read.csv(file = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/keatonwilson/beans/master/data/bean_master_joined.csv?token=AefUVEvB38PXHx8ExMoim-IlgrhsKthtks5bq7KuwA%3D%3D")

#Let's cut down the data frame to only the important bits

bean_ML_imports = bean_master_import %>%

mutate(month = month(date),

day = day(date)) %>%

select(future_weekly_avg_price, price, class, whole_market_avg, class_market_share,

planted, harvested, yield, production, imports, date, month, day) %>%

filter(!is.na(future_weekly_avg_price))

bean_ML_imports$class = factor(bean_ML_imports$class)

bean_ML_imports$month = factor(bean_ML_imports$month)

bean_ML_imports$day = factor(bean_ML_imports$day)

#Setting seed for reproducibility

set.seed(42)

#Preprocessing

preProc2 = preProcess(bean_ML_imports[,-c(1,11)], method = c("center", "scale", "knnImpute", "zv"))

bean_ML_import_pp = predict(preProc2, bean_ML_imports[,-c(1,11)])

#binding the response and dates variable back on

bean_ML_import_pp$future_weekly_avg_price = bean_ML_imports[,1]

bean_ML_import_pp$date = bean_ML_imports[,11]

#Training and test sets

index1 = createDataPartition(bean_ML_import_pp$future_weekly_avg_price, p = 0.80, list = FALSE)

bean_ML_import_train = bean_ML_import_pp[index1,]

bean_ML_import_test = bean_ML_import_pp[-index1,]The output of this chunk of code above is what we’re going to work with - specifically, the test set - which means that the simulation we’ll run will be completely on out-of-sample data, which should provide a more realistic set of predictions.

We need to do a few things before we get into the nitty-gritty of building the model though: first, we need to get rid of duplicate rows - which simplifies our simulation a lot. Instead of making decisions among all of the varietals for a given week that might give the best return on investment, we’re going to set up a simple scenario where we only look at weeks where there is one option - and then decide whether to buy or not. This next code chunk also a few other details - we’ve loaded our previously-built model as an RDS object, and then use it to bind predictions back onto the data frame.

#Renaming

bean_portfolio = bean_ML_import_test

#binding non-transformed prices back on.

bean_portfolio$nontran_price = bean_ML_imports[-index1,]$price

#RF Model is on final_model.rd - this will be locally in your machine, it's the model object we built a few posts back

#

super_model = readRDS(file = "/Users/KeatonWilson/Documents/Projects/beans2/final_model.rds")

#binding predictions onto the test data frame

bean_portfolio$pred = predict(super_model, bean_portfolio)

#Generating a column to say whether or not the date is a duplicate

bean_portfolio$dup = duplicated(bean_portfolio$date)

glimpse(bean_portfolio)## Observations: 1,339

## Variables: 16

## $ price <dbl> -1.59998660, -1.24329275, -1.43785303,...

## $ class <fct> Pinto, Pinto, Pinto, Pinto, Pinto, Pin...

## $ whole_market_avg <dbl> -1.4308377, -1.2062523, -1.2553069, -1...

## $ class_market_share <dbl> -0.16479201, 0.27002425, 0.12468812, 0...

## $ planted <dbl> 1.690830, 1.690830, 1.690830, 1.690830...

## $ harvested <dbl> 1.802003, 1.802003, 1.802003, 1.802003...

## $ yield <dbl> -0.5926519, -0.5926519, -0.5926519, -0...

## $ production <dbl> 1.771990, 1.771990, 1.771990, 1.771990...

## $ imports <dbl> 1.8751095, 1.8751095, 1.8751095, 1.875...

## $ month <fct> 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 1, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 1...

## $ day <fct> 28, 16, 11, 15, 3, 20, 26, 2, 15, 14, ...

## $ future_weekly_avg_price <dbl> 17.13, 16.37, 16.00, 17.88, 19.00, 32....

## $ date <fct> 1987-04-28, 1987-06-16, 1987-08-11, 19...

## $ nontran_price <dbl> 17.50, 20.25, 18.75, 18.38, 17.00, 16....

## $ pred <dbl> 17.50913, 16.58924, 16.44968, 17.55849...

## $ dup <lgl> FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FAL...#Paring it down

small_bean_portfolio = bean_portfolio %>%

filter(dup == FALSE) %>%

arrange(date)Building the model

bank = 10000 # initializing our starting value

df_port = list() #initializing the list that we'll output to

unique_dates = unique(small_bean_portfolio$date)

'%w/o%' <- function(x,y)!('%in%'(x,y)) #making a 'without' funcion

for(i in 1:nrow(small_bean_portfolio)) {

subset = small_bean_portfolio[i,] # pulling out a row, indexed by row number

df_port$Date[[i]] = as.character(subset$date) # feeding in the iterated date to the output data frame

max_spend = 0.33*bank #figuring out how much we can spend on beans

buy = ifelse(subset$nontran_price < subset$pred, TRUE, FALSE) #Deciding whether to buy or not buy, based on whether the predicted price is more than the current price

if (buy == TRUE) {

num_100wt = ifelse(floor(max_spend/subset$nontran_price) > 10^5, 10^5, floor(max_spend/subset$nontran_price)) #Calculating the number of hundred-weights we can afford (capping at 10^5 hundredweights based on domain knowledge)

df_port$num_100wt[[i]] = num_100wt #binding this to the output dataframe

amount_spent = num_100wt*subset$nontran_price #calculating the amount of money we spent on beans

df_port$amount_spent[[i]] = amount_spent #binding this to the output dataframe

amount_made = subset$future_weekly_avg_price * num_100wt #Calculating amount made

df_port$amount_made[[i]] = amount_made #binding to data frame

bank = bank - amount_spent + amount_made #subtracting our costs and adding our profits to update bank

df_port$bank[i] = bank #binding to the output dataframe

}

else {

df_port$num_100wt[[i]] = NA

df_port$amount_spent[[i]] = NA

df_port$bank[[i]] = bank

df_port$amount_made[[i]] = NA

}

}

#binding the output list into a dataframe

df_port_df = dplyr::bind_cols(df_port)

dplyr::glimpse(df_port_df)## Observations: 763

## Variables: 5

## $ Date <chr> "1987-01-13", "1987-01-21", "1987-01-27", "1987-0...

## $ num_100wt <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 160, NA, 198, NA, NA, NA,...

## $ amount_spent <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 3280.00, NA, 3465.00, NA,...

## $ bank <dbl> 10000.00, 10000.00, 10000.00, 10000.00, 10000.00,...

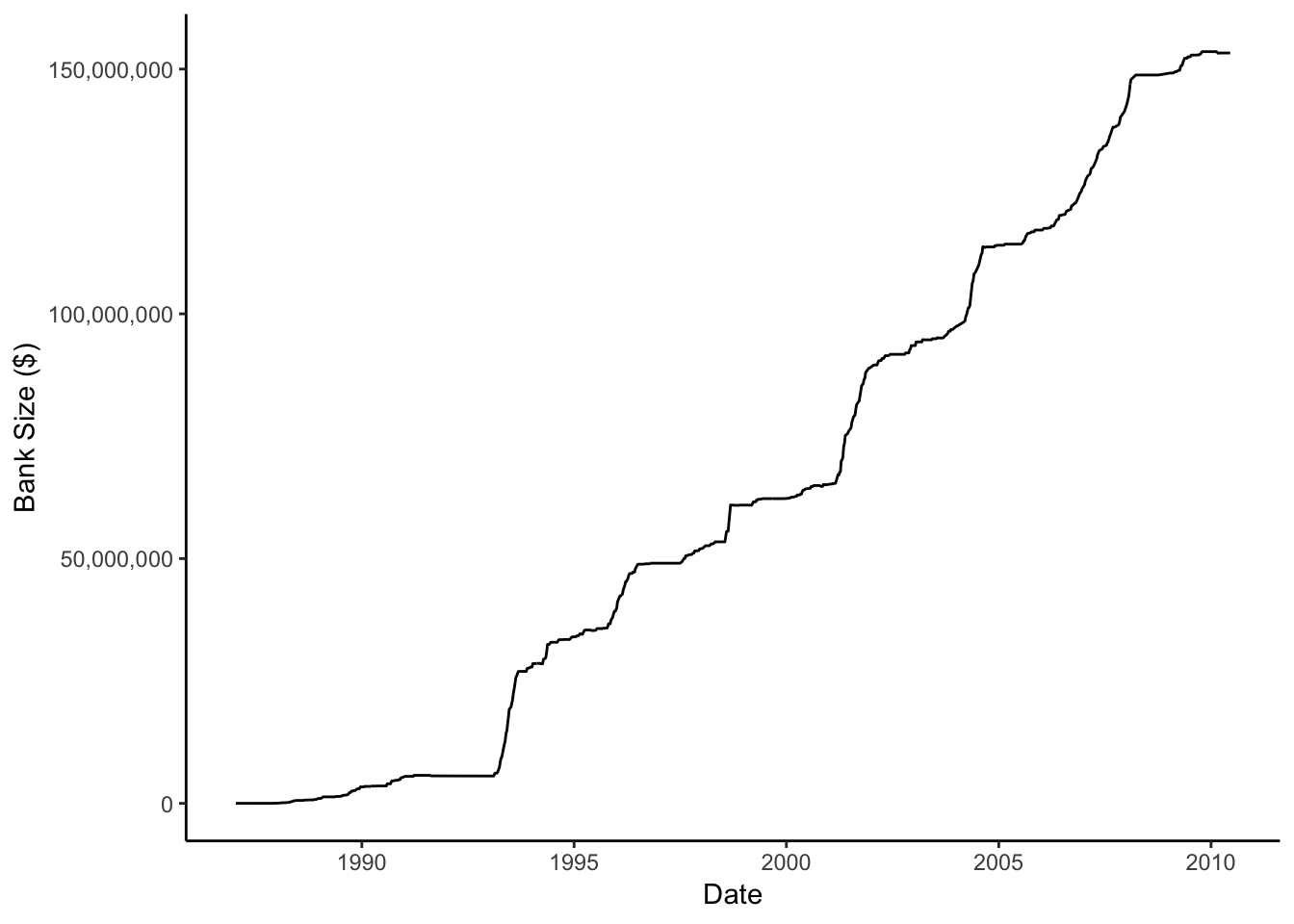

## $ amount_made <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 3800.00, NA, 3391.74, NA,...Great! Now let’s visualize how our bank size grows over time!

ggplot(df_port_df, aes(x = as.Date(Date), y = bank)) +

geom_path() +

ylab("Bank Size ($)") +

xlab("Date") +

theme_classic() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = comma)

Whoa! So if we had conservatively purchased based on the rules of this simulation and had our predictive model in hand since the 80s, we could have turned our $10k into 150,000,000. Not too bad. We can also look and see how many times our model steered us wrong and we lost money.

df_port_df %>%

filter(amount_spent > amount_made) %>%

mutate(amount_lost = amount_spent - amount_made) %>%

arrange(desc(amount_lost))## # A tibble: 29 x 6

## Date num_100wt amount_spent bank amount_made amount_lost

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 2010-03-02 100000 4075000 153231547. 3750000 325000

## 2 2004-09-08 100000 2900000 113561547. 2750000 150000

## 3 2000-10-24 100000 2350000 64749547. 2225000 125000

## 4 1991-08-20 94490 1889800 5620416. 1783499. 106301.

## 5 1995-03-14 100000 2600000 34536547. 2500000 100000

## 6 1995-05-30 100000 2175000 35311547. 2075000 100000

## 7 1994-03-22 100000 3300000 28511547. 3213000. 87000.

## 8 2001-03-27 100000 2650000 67049547. 2575000 75000

## 9 1995-08-29 100000 2600000 35661547. 2550000 50000

## 10 1998-09-29 100000 2525000 60899547. 2475000 50000

## # ... with 19 more rowsYikes, some heavy losses, particularly in the 90s and early 00s, with the biggest of $325k in March of 2010 - but, when you’ve got 153 million in the bank, it’s not as drastic as it seems.

Conclusions

Hopefully this was an interesting example of the power of leveraging the ML model to predict real-world data. The simulation clearly illustrates the predictive power of the model, but also has a few built-in assumptions that are worth mentioning:

- We aren’t making choices among varietals each week (i.e. do I buy pintos or garbanzos, even when the model predicts both will turn a profit) like a real broker would. I initially went down the road to try and simulate this, but got stuck in the code - something I’d like to revisit some day soon.

- One BIG assumption is that you’re able to sell all of the beans you buy. It may not always be so easy to totally liquidate all of your beans at a certain price.

- There aren’t any costs associated with holding beans here - in the real world, you’d have to warehouse them, and transport them somewhere, all which come at a price.

Regardless, an impressive display of prediction!

Cheers!